Like many people, I have always taken comfort in watching old movies. From noir to awe-inspiring technicolor musicals, classic films were like comfort food for me. But as I grew older–and grew into my feminism–I began to observe that rapes, assaults, objectification and degradation of women and egregious racism are featured in some of these films. Many film-lovers dismiss modern criticism, saying that these films were “products of their time.” In response to this approach, Melissa Silverstein, founder and publisher of the website Women and Hollywood, told me, “It is about time for us to be revisiting the canon, the films that have been revered, taught and emulated for decades without question. We have progressed to be living in a world where behaviors regarding women and people of color that passed without question are now being challenged.”

Thanks to the #metoo and #timesup movements shining a spotlight on problematic Hollywood behavior, this is the perfect time to reconsider classic films and acknowledge some of the moments and themes that make us uncomfortable.

Gone With the Wind (1939)

Despite its status as a beloved classic and as a multiple Oscar-winner, there’s a lot to cringe at. The film is also drenched in racism and social propaganda, but with the #metoo lens, our focus is on the “love story” between Scarlett O’Hara and her husband Rhett Butler. Scoundrel Rhett (played by Clark Gable, known to have behaved problematically around women off-screen as well) is supposed to be irresistibly charming, but in one very uncomfortable scene, maritally rapes Scarlett (Vivien Leigh): she visibly fights him off as he carries her upstairs to the bedroom. The next scene shows Scarlett the morning after, in bed, glowing, singing and happy. There has been considerable dissent about this scene, whether Scarlett viewed it as rape (and if that matters), and whether it reflects the reality of women in that time being considered as the property of their husbands (and if THAT matters). We can even talk about how Rhett “apologizes” to Scarlett after (a terrible apology ultimately ending with him asking her for a divorce, taking their child, and threatening to beat her). But however you slice it, it’s hard to watch today.

However, there is still merit in Gone With the Wind. The film won an Oscar for Hattie McDaniel, making her the first African American actor to ever receive that honor, and it was also one of the first blockbuster movies to use color for the duration of the film. Also, though steeped in their traditional roles, Scarlett, Melanie, and even Mammy are all strong characters.

The Philadelphia Story (1940)

This romantic comedy starred the three biggest names at the time: Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, and Jimmy Stewart. Socialite Tracy Lord (Katharine Hepburn) is about to be married when her ex-husband C.K. Dexter Haven (Cary Grant) and tabloid reporter Mike Connor (Jimmy Stewart) interfere with her plans by declaring their own romantic interest for her. This follows the genre of “comedy of remarriage” that was popular in the era. A couple divorces, the exes flirt with other people, before ultimately getting back together and remarrying.

This film is considered a timeless comedy, but some sexist overtones may prompt modern audiences to reconsider what they’re laughing at. While the leading lady is played by the feminist and independent Katharine Hepburn, her character’s high standards are perceived as a flaw. For example, in the opening scene, when Grant’s character is leaving the house with his suitcase, Hepburn follows him out and breaks his golf clubs in front of him. Grant threatens to punch her, instead pushing her to the ground. This is supposed to be the “comedic” opening. Throughout the film, Hepburn constantly calls out the men in her life on their bad behavior (extramarital affairs, abuse of alcohol, just being jerks, etc) and they counter that by saying she’s being “haughty, frigid, and unforgiving.” This is the classic double standard: when a man calls someone out, he’s called “honest” or “take charge.” Grant’s character even blames Hepburn’s for his alcoholism, which is abuse. In the end, the men don’t change their ways, but it’s Tracy who has learned the lesson, saying she’ll be more forgiving and not judge people. The “happy ending” only comes when the woman in the story submits to the men.

But The Philadelphia Story’s cultural impact endures: It’s ranked number five on the American Film Institute’s list of Top 10 Romantic Comedy Films, and won two Academy Awards, one for Best Actor (Jimmy Stewart) and one for Best Writing, Screenplay (Donald Ogden Stewart).

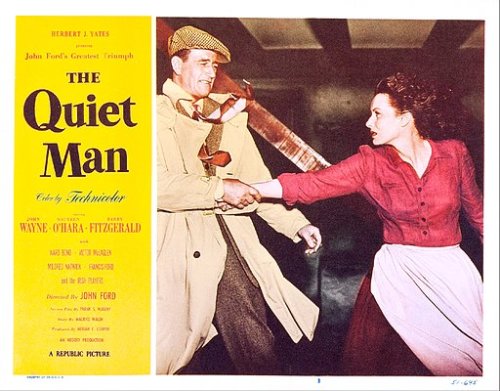

The Quiet Man (1952)

One of John Wayne’s few non-Western roles, and his only true romantic comedy, The Quiet Man had a lot going for it. Shot on location in lush Ireland, the film centers on a culture shock love story between an Irish-born American, Sean Thornton (Wayne), and a traditional, feisty Irish woman, Mary Kate Danaher (Maureen O’Hara). This is a favorite in many families with Irish heritage and often airs on TV for St. Patrick’s Day. The Quiet Man won two Academy Awards: one for Best Director (John Ford) and for Best Cinematography. It has made many pop culture appearances in other films from E.T. to Brooklyn. The visuals of Ireland are beautiful and it is one of the few Hollywood films to have Gaelic–the native Irish language–spoken.

But through our modern lens, we have to mention two things:

- After Mary Kate refuses his advances on their wedding night, Sean breaks down the door and says “there’ll be no locks or bolts between us Mary Kate…except those in your mercenary little heart!” as the camera fades out, fading back in for the next scene featuring a happy Mary Kate (frankly, Scarlett, we see a pattern of implied marital rape…).

- When Mary Kate leaves Sean, he literally drags her five miles into town, throwing her around like a rag doll. The townspeople watch gleefully because the prideful Mary Kay is finally “getting what’s coming to her.” After this public humiliation, a beaten-down Mary Kate goes home to prepare her husband’s supper. (A decade later, in McLintock, Wayne’s character also beats O’Hara’s to public cheer.) Where’s the comedy?

Gigi (1958)

Who doesn’t love a good old-fashioned musical? The bright colors, the emotional songs and dances, the elderly man sitting in a park full of children singing “Thank Heaven For Little Girls”? That’s our introduction to Gigi: a “love story” between an adult male and a young girl in training to become a “courtesan” (a fancy word for mistress) in high society. There’s a special (and creepy) focus on Gigi being “girlish” and “childlike,” and Gaston, her “love interest,” publicly humiliates his former mistress to the extent that she attempts suicide. However, Gigi is still considered the last great MGM musical, and won nine Academy Awards, winning all categories in which it received nominations. It is also notable because Arthur Freed, the film’s producer, battled the Hays Code (a set of moral guidelines applied to films from 1930-1968) for years to get this film produced; after the Code fell into disuse, the Motion Picture Association of America developed the rating system for films (G, PG, R and X, and later PG-13 and NC-17) that we know today.

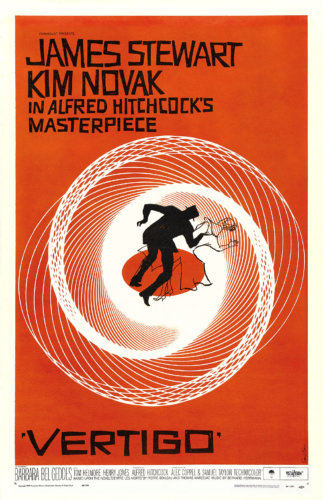

Vertigo (1958)

One of Hitchcock’s most famous movies, Vertigo was the first film to use computer graphics and the first to use the “trombone shot,” invented for the film in order to create a sense of vertigo for the audience. Both are still used in movies today.

The plot, however, challenges the modern eye. Scottie (Jimmy Stewart) is a former police detective with a paralyzing fear of heights being hired to follow Madeleine (Kim Novak), who has been acting strangely. Madeleine discovers Scottie has been following her, and they spend a lot of time together and ultimately fall in love. After expressing their love for each other, Madeleine runs into the church and jumps off the bell tower to her “death.” Scottie has a nervous breakdown and has to be taken to a sanitarium. When he is released, he runs into Judy (also played by Novak) who reminds him of Madeleine. Scottie follows Judy around, breaking into her apartment, forcing her to change her hair and clothes until she looks like Madeleine. He then forces her to confess that she and Madeleine are the same person. The film ends with Judy accidentally falling to her death, a chilling reminder that male obsession and aggression often ends with women paying the price. Or as Agata Frymus, a film and media graduate, wrote in her article on the f-word, “In Vertigo women are made the villains and are the ones that need to be punished in order to restore peace and sanity for men.” In fact, Kim Novak, as the “object” in the film, doesn’t speak until more than a third into the action.

These films are part of a rich cinema history, and could not have reflected a future they hadn’t yet seen. But from our perspective, looking back on these cultural works through a modern lens, we need to see these films for both their achievements and their missteps.

Grok Nation Comment Policy

We welcome thoughtful, grokky comments—keep your negativity and spam to yourself. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.