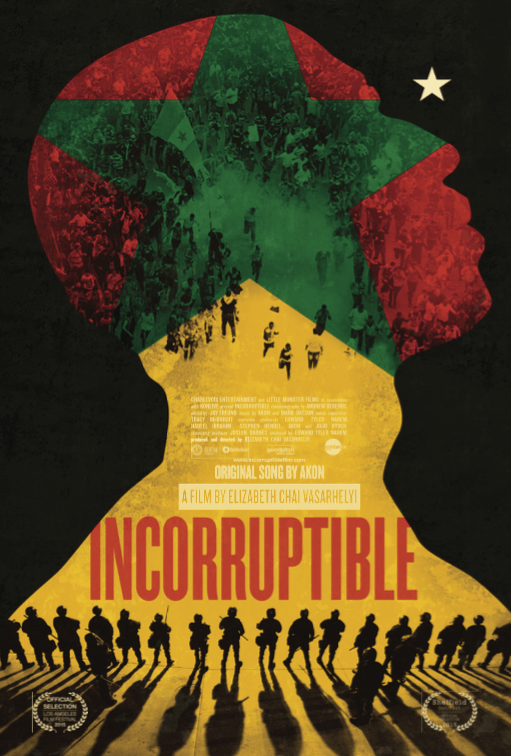

Mayim Bialik: In a nutshell, what is your film, Incorruptible, about?

Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi: Incorruptible looks at the 2012 Senegalese elections. Senegal is one of the oldest democracies in Africa and the incumbent president at the time changed the Constitution to allow for a third term [in order for him to maintain power and be re-elected]. And this kind of rocked the foundation of society: in a stunning youth movement which was led by pop rap artists, people came out to protest the change in the Constitution as well as advocate for a new candidate.

MB: How did you first get involved in documentary filmmaking in general and then specifically with this project?

ECV: I began making my first documentary film as an undergrad at Princeton. I was an editor of a newspaper there and the war in Kosovo broke out. And for me, who had known so much about what happened in Bosnia, I couldn’t really understand how there was still conflict in Kosovo so many years later. So, along with a fellow student, we went over there and began making a film, not knowing much about how to make a film. And that’s how I began making documentary film. I kind of never looked back.

Regarding the making of Incorruptible, I have very old film-making ties to Senegal. I made my second film in Senegal and it was very much motivated by a response to 9/11. Senegal’s biggest pop star, Youssou N’Dour is this world figure and he had come out with this album that celebrated a peaceful side of Islam and I thought that was fascinating at the time and that he had a story that had to be heard by a lot of people. It’s called Youssou N’Dour: I Bring What I Love.

I subsequently made another film in Senegal about religion. I had these ties to the place and I had a very unique access, so when the constitutional change transpired in 2012, the subject of my first film began running for president. I knew that he probably wouldn’t get elected but I also knew the incumbent president quite well. So I had this very privileged access to all the parties [and] the protections of being an outsider, so it was just kind of like a perfect storm; documentaries are all about access to gaze or the way you look at it. In addition, I felt very personally invested, because I knew Senegal very well and it was transformed overnight by violence due to people’s constitutional rights being threatened, so I was personally compelled to get involved.

MB: Today, many people are concerned with what’s going on in our country because of some very blatant and very clear challenges to the structure of our Constitution – in particular, the way the checks and balances have been established and the way that protecting the rights of the people have been insured. I want to know if you think there are specific lessons that we in the U.S. can learn from Incorruptible, in terms of the concerns many people have about our constitutional rights right now?

ECV: At the Cinema Eye Awards, an old friend of mine and filmmaker named Marshall Curry, who made the film about Cory Booker’s election, Street Fight, was speaking and he simply said, “Cynicism is complacency.” And for me it was like a lightbulb went off in my head because I think that’s one of the lessons from Incorruptible. In Senegal in 2012, people refused to stand down. They said, “We will stand up for our rights. We will definitely make sure our voices are heard.” The lesson is they were able to actually affect a change. They elected a new president and that was remarkable. Because I went into it thinking, ”Oh, there’s no way that the incumbent president is going to lose. It’s just too entrenched. He’s got too much power.”

Even as these protests started rocking the country and it got very violent, they had this faith in the strength of their institution. And the institutions held up. They were able to exercise their right and vote out a president and vote in a new one. The oldest democracy in Africa, but it’s still that fragile and also the democracy can be violent. And that’s terrifying. It’s been hard trying to wrap my own head around what’s transpired in this country and I look at these voices from Senegal who live in this time of dramatic economic downturn: very few opportunities, [and] the educational system is crumbling and yet this pride; constitutional pride, civic pride and political pride of who they are. How their identity is intertwined with being from a democracy in Africa. It was so important that they are unwilling to accept that this essential corruption within their political system.

I think it’s super-timely. It’s a time for action. At the same time, I get sad because in terms of documentary filmmaking, I feel we’re all doing a really good job and then I get kind of bummed out because what else can we do? I feel like all my peers are doing such a good job trying to represent a story, trying to make voices heard, trying to highlight social issues, political issues and I worry that we’re really disconnected.

MB: I’ve heard many people saying that celebrities have no place having an opinion about politics and they should shut up. Your film shows public people who were at the forefront of this movement, I wonder if you have any comment about that?

ECV: Yes, they were celebrities in their own communities however, and they were also individuals of great integrity and authenticity. I have so much respect for the way the members and leaders of the Y’en a Marre [the opposition organization] conducted themselves, They used their voice to make an issue heard and they acted with such integrity and self-restraint. The whole point of the Y’en a Marre was peaceable resistance, non-violent resistance. They would have sit-ins of thousands of people. I think especially in this day and age where social media is so potent, there’s a lot of things coming at you. I personally think if you have that platform, you have to use it. But the point is, use it with integrity and principle and ethics. You have to be responsible about what you’re advocating. I think we should use every tool available to us to make our voices heard regarding the things that mean the most to us. I think what you’re doing is fantastic.

MB: I appreciate that. But obviously, there’s just about half the country that doesn’t think that I or anyone else should have anything to say. So it’s a difficult thing in deciding what role everyone has, but when it comes to defending people’s rights and defending the right of people to live how they want, I’m pretty much prepared to keep fighting this for the rest of my life…Where can people get your film? We want to make sure that we have all the information we need so they can see it.

ECV: They’ll be able to watch it on Netflix in the spring.

MB: Great, we will remind all of our readers about it then. Thank you so much and I really look forward to getting your film out there.

ECV: Thank you!

For more about Senegal, see this from AJWS.

Read More From Mayim

Read More From Mayim

Grok Nation Comment Policy

We welcome thoughtful, grokky comments—keep your negativity and spam to yourself. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.