Imagine, for a moment, that you’re a stranger adjusting to life in a new city. You’ve recently moved hundreds of miles from the bustling river town where you spent the past 20 years of your life, raising your three sons. You are one of the few women making a home in this lonely, windswept corner of a frontier territory.

With enough regularity for the neighbors to take notice, your husband comes home drunk from one of the many saloons lining your new town’s tiny main drag. Sometimes he hits you. But there are no laws against this, not in the place where you now live, and not in the state you just left behind.

A year after you arrive, word comes from the capitol 300 miles south that women have been given the right to vote for the first time in your country’s history. You express your approval and excitement in conversations around town and to the local politician who had a hand in passing the bill. Then a circuit court judge reaches out. He wants to talk to you about the new legislation. But it isn’t your opinion he’s after. He wants to appoint you Justice of the Peace, overseeing legal cases in your newly adopted city. You’ve just been asked to become the first woman in United States history to hold public office.

Would you say yes?

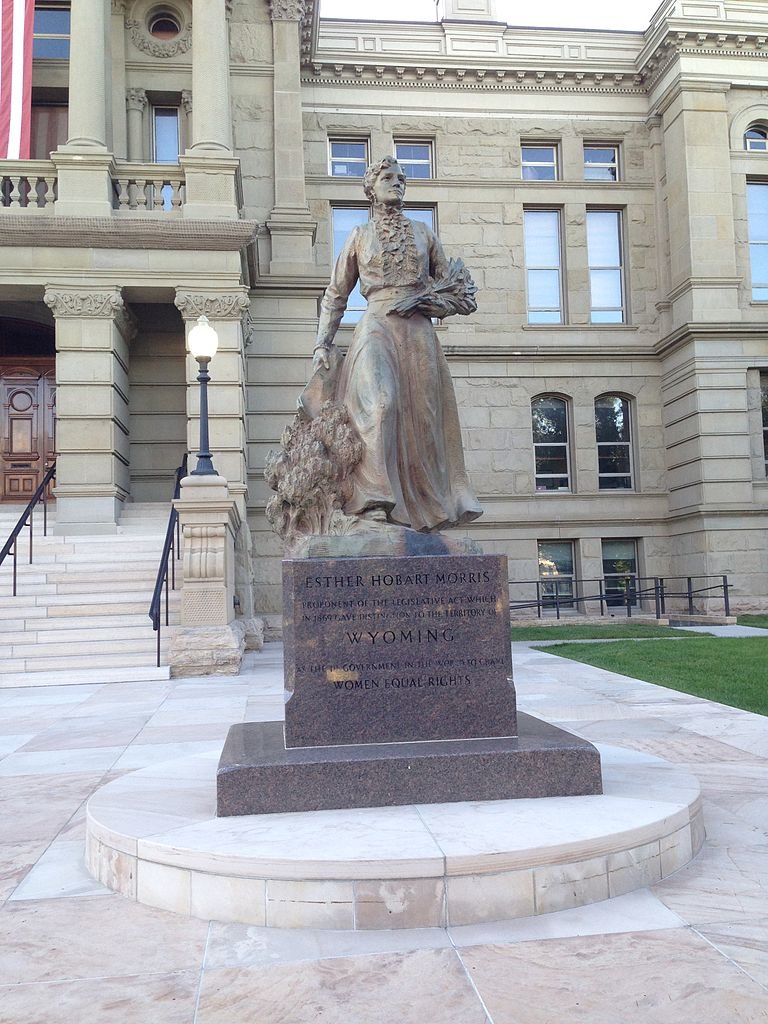

Esther Morris almost said no. She’s the real-life woman who arrived in South Pass City, Wyoming, in 1869 and became the country’s first female Justice of the Peace just a year later in a bizarre twist of fate. History could have been much different if she hadn’t eventually given in to the serious persuasion it took for her to accept. Yet Morris is no less admirable for being a reluctant heroine. If anything, it makes the way she stepped up—and what happened after–all the more remarkable.

In the years following Morris’ brief eight-month term in office, a rich mythology grew up around her. In this fanciful version of history, it was Morris who successfully lobbied for the suffrage bill, charming Wyoming legislators as she plopped sugar cubes into their tea cups. The revisionist impulse is understandable. It would make a neater, nicer story for the godmother of women’s suffrage to have played a more active part in paving the way for her historic term. The truth is, though, that while Morris agreed with the rhetoric of early women’s rights leaders like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and supported abolition before the Civil War, Morris didn’t make suffrage her life’s work. She didn’t get arrested for voting like Susan B. Anthony, or go on a hunger strike for equality like Alice Paul. She wasn’t brought up in the well-to-do, highly educated Quaker culture that produced many of America’s early suffragettes.

Instead, the first 50 years of Morris’ life was much the same as millions of other American women of her day. She supported herself with sewing after her parents died when she was a young girl. She lived with her grandparents until she married in her late 20s, had a son, and was widowed by the time she was 30. Morris moved to the young Midwestern steamboat town of Peru, Illinois, in hopes of supporting herself and young child with some property her husband left behind. According to the law in 1840s Illinois, however, Morris was a “perpetual juvenile” with no right to control her husband’s property.

Nevertheless, she persisted. Morris managed as a single mother for six years before marrying a man named John Morris in 1851. With remarriage, however, came another injustice from the laws of the day. There’s no official record of when John first hit Esther, but there is evidence to suggest he did. Domestic violence was perfectly legal in Illinois at the time—and in most of the country, for that matter. Tennessee was the first state in the country to ban “wife beating” with an 1850 law that remained unique until the end of the century.

In 1868, John decided to see if he could strike it rich in a booming gold town perched high in the Rocky Mountains. He left with Morris’ eldest son, Archy, and she followed a few months later with the twins she and John had together. Unbeknownst to them, there was something bigger going on in Wyoming than gold.

Wyoming’s Democratic legislators were tossing around the idea of granting women the right to vote, in part to bolster their chances of staying in office, and in part to market the far-flung young territory as a kind of feminist utopia. None of the men floating the bill took suffrage seriously on its own merits. If anything, they found it just as laughable as the new federal laws that had been passed giving millions of newly freed black men the vote.

The suffrage bill narrowly passed at the tail end of 1869—a full 50 years before the 19th amendment would give women the right to vote coast to coast. The Justice of the Peace in South Pass City resigned in protest. That left an important judge’s seat open, though, as well as an opportunity to see what would happen if a woman were actually put into office. And there was one woman in particular who lived in South Pass City, supported suffrage, and seemed to have the grit for the job.

For the first time in her 55 years, Esther Morris was a full and equal citizen. She acted accordingly and gave her tiny mining community a taste of the future. When her predecessor refused to turn over his official paperwork and dockets, she had him arrested. When her husband decided to express exactly what he thought of his wife’s new job by giving her a beating, she had him sent to jail, too. Morris might not have been to high school or college, much less law school, but she excelled as a judge. In her eight months in office, not one of her rulings was successfully overturned.

Despite her success, none of the men who had put her into office thought the experiment should go beyond one term. Morris’ appointment was not renewed. At first, life seemed to return to normal, but there was no going back. In 1871, Morris left both South Pass City and her husband. She spent the final third of her life living on her own terms, her name suddenly on the lips of the same women’s rights thinkers and agitators she’d admired for decades.

The way Morris lived in her final decades clearly shows that our wants and needs as women haven’t changed so very much in the past 150 years. While we’ve come a long way since Morris’ day, we are still fighting for many of the same rights she lacked for most her her life—to have a voice in our communities, to control our own finances and affairs, to live free of violence.

Despite offers and inquires, Morris declined to run for office again. Instead, she attended women’s rights conventions and served as vice president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1876. When Wyoming became a state in 1890, Morris played a role in the ceremony, accepting the brand new flag of the Equality State. Though she traveled regularly and spent winters back east, she ultimately retired near one of her sons in Cheyenne, Wyoming, and died in 1912.

Esther Morris is no longer a household name outside of her adopted state, and her role in women’s history isn’t as well remembered as it once was. Yet it is her very rise from obscurity and slow fade back into it that serve as an important reminder to modern women that one doesn’t need to be extraordinary to make an impact. All that’s required is the willingness, however unsure at first, to step up and try something new.

Grok Nation Comment Policy

We welcome thoughtful, grokky comments—keep your negativity and spam to yourself. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.