All the Women in My Family Sing is a new book centering on one idea: women telling their stories. In honor of Black History Month, we share the essay titled “From Negro to Black” by La Rhonda Crosby-Johnson from the book.

Colored was coming to an end. I’d be a Negro, they told me, like the young preacher who led a bus boycott, the woman who sat down and made America stand up, the Harlem minister with an alphabet for a last name. “Colored” and “Whites Only” signs over water fountains and public facility entrances were coming down all over the American South. The front of the bus was all ours! The next-door neighbors might even one day be white. My grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles stood a little taller, held their heads a little higher. They had been Colored a long time and had been called worse even longer.

Since this Negro thing was new to all of us, we wanted to make sure we got it right. We stopped talking too loudly in public places, made sure never to wear our house shoes outside. On Sunday mornings, we placed neatly pressed and folded handkerchiefs in our patent leather pocketbooks. On Monday mornings at school, the new Negro children stood tall in straight Negro lines while we waited for our Negro teachers to retrieve us from the playground. The new Negro adults wondered where this thing would take us. Would we be able to vote without guessing the number of jelly beans in a jar or the number of bubbles in a bar of Ivory soap? The Negro men all hoped for better jobs with pay equal to their new white “brothers,” or at least something a little more than they made when they were Colored.

I was just about getting the Negro thing down when the world turned Black. Huey Newton. Angela Davis. The old schoolyard adage “If you’re white, you’re all right; if you’re Black, get back” was quickly replaced with “Black is beautiful, brown is hip, yellow is mellow and white ain’t s*#t.” Negro History Week expanded into Black History Month. The slow and way-too-patient Civil Rights Movement began to make us frustrated, as our sons were forced to fight a war against a people who had never done them any wrong. These now Black people recognized that the removal of “Colored” and “Whites Only” signs didn’t grant the access they had dreamed about and marched for, and that the right to vote meant nothing without something for which to vote.

I watched my parents, who had once been Colored, struggle to decide if being Black might be an improvement over Negro. Did these loud, bold, proud, fearless, gun-carrying, Constitution-quoting young people have the answer? Had the marchers, bus boycotters and We-Shall-Overcomers missed something?

I certainly felt more at home in my new Black skin than I did during my brief time as Negro. No more burned necks and ears from a scorching hot comb. The afro meant no more Saturday mornings hoisted onto two telephone books while Mama “worked with my kitchen.” Now my kinks were beautiful. Afro Sheen said so every Saturday morning as I attempted to imitate the dancers on Soul Train.

It soon became evident that the end of Negro was going to be difficult. For our once-Colored-then-Negro-now-Black selves, change meant that the man who had declared “I have a dream” would be shot dead on the balcony of a Memphis hotel, while revolutionaries were spied on and killed in their sleep.

The chant “Burn, baby, burn” was accompanied by Molotov cocktail fire that left our neighborhoods in ashes. The government that prided itself in touting “We the People” certainly didn’t have us in mind. Black was definitely beautiful: We had a Miss Black America contest, after all, but it looked like this change was going to take a lot more than a new hairstyle and a dashiki.

I wanted to get this Black thing down in a way that would make my people not only proud, but strong. I began to study “Black”—searching out Maya Angelou, Richard Wright and Langston Hughes in my junior high school library. It meant Mama signing the permission slip necessary to check out The Souls of Black Folk and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. I had never needed a permission slip to check out Little House on the Prairie or a Hardy Boys book. My parents nurtured my new Blackness, challenging me to challenge everything. So, when Mama signed her third permission slip, she included a note telling the librarian, “Let La Rhonda read what she wants to read!” My mother and father somehow knew it would be my Blackness that would raise the next generation, long after hairstyles changed and fists once held high in solidarity and defiance were lowered.

We’ve moved on from Black to African American. While I like the geographical connection to Africa, a continent I have yet to visit, Black always felt like home. I raised an African American son who was compelled to learn to navigate the world without an entire movement behind him, since we were done with Black by the time he arrived.

I watched the pride we felt “back in the day” dissolve as our race desired better jobs and bigger houses in “better” neighborhoods—code for No Black Neighbors, Please. We whispered our “Blackness” and hid as much of it as possible in a multi- racial, multiethnic, multicultural stew that had no flavor. We hungered for acceptance to white schools and the chance to wear $200 basketball shoes named after athletes who hoped they could somehow make their Blackness invisible by jumping higher and staying in the air longer. It seemed our favorite color had gone from Black to green.

The journey from Negro to Black was quite a ride. Now, here I am, African American in a time overflowing with achieve- ments that were marked “First”—America’s First Black President. There were sorrows that made us weep and wail, as we donned wristbands with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter. We marched and protested and stood before tanks to con- vince those who would shoot us and leave us dying in the streets, those who would use the power of their badges to imprison and rape us, that we are here to stay. We still need the courage to stand when others run away and to develop tools to fight enemies more cunning and violent than the KKK of my Colored grandparents. We still need to hope, to dream, this time with our eyes wide open and grounded in the realities of continued division. There will be better days for my people. There will also be days when we wring our hands and wonder if we weren’t going backward instead of forward.

It doesn’t matter if you proudly check the box next to “Black/ African American” or make a list of your genealogy next to the “Other” box. What matters is where we go from here. What is the responsibility of those who traveled from Negro to Black to African American? How do we make this entire trip mean something long after we’re gone? We stand.

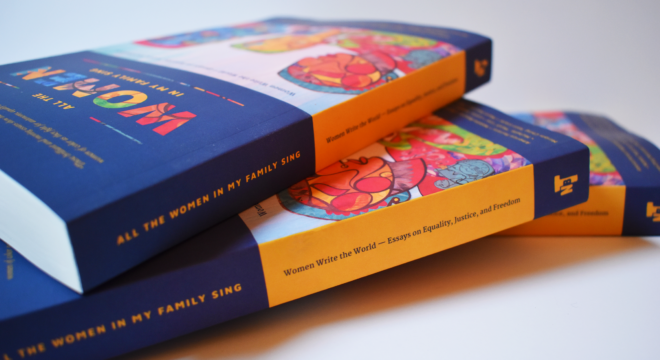

All the Women in My Family Sing is full of many essays like the one above, by women of all cultures and walks of life—including actress America Ferrera and Queen Sugar writer Natalie Baszile. The essays touch on cultural identity, sexuality, immigration, careers, social justice, and family. You can purchase the book on Amazon.

La Rhonda Crosby-Johnson is an educator, writer, certified Integral Coach and founder and CEO of BARUTI Enterprises. She is dedicated to creating and supporting environments for transformation. She was born in Oakland, California, and was a product of Oakland public schools before entering San Francisco State University. She received a bachelor’s degree in social work in the winter of 1984. La Rhonda, a much-sought-after speaker and facilitator, is proud of her nearly thirty-five-year career, which has focused on women’s wellness, providing access to health care, reproductive rights, community development and education. She is currently working on a novel and establishing a publishing company.

La Rhonda Crosby-Johnson is an educator, writer, certified Integral Coach and founder and CEO of BARUTI Enterprises. She is dedicated to creating and supporting environments for transformation. She was born in Oakland, California, and was a product of Oakland public schools before entering San Francisco State University. She received a bachelor’s degree in social work in the winter of 1984. La Rhonda, a much-sought-after speaker and facilitator, is proud of her nearly thirty-five-year career, which has focused on women’s wellness, providing access to health care, reproductive rights, community development and education. She is currently working on a novel and establishing a publishing company.

“From Negro to Black” by La Rhonda Crosby-Johnson is excerpted from the book All the Women in My Family Sing: Women Write the World — Essays on Equality, Justice and Freedom. Reprinted with permission of Nothing But The Truth Publishing, LLC. Copyright 2018 edited by Deborah Santana.

Grok Nation Comment Policy

We welcome thoughtful, grokky comments—keep your negativity and spam to yourself. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.