When it comes to those topics that are difficult for even adults to discuss, what can I do? How do I talk to my kids, ages 3 and 5, about school shootings? Death? The environment? Immigration? Race? Class? Gender? Politics?

My answer: Books.

I know that I can’t solve the world’s problems by reading to my kids. But I also know that if I can get them to make connections between what they read and what they see and hear, they’ll have a context for understanding the world—its goodness and its terror.

When Hurricane Harvey hit in August, my 3-year-old daughter first heard about it on the car radio.

As we heard the emergency shelter plan, my daughter yelled from the backseat, “Mommy, what’s a shelter?”

At 70 mph on the highway, I wasn’t expecting it, but I knew exactly how to explain it.

“Remember in Last Stop On Market Street, when CJ, the little boy, doesn’t want to ride the bus with his grandma at first, but then he does because they go to a soup kitchen, where they help out?” I shouted.

“Yeah,” she said.

“A soup kitchen is like a shelter. It’s a place people can go when they need some help with a place to stay or something to eat,” I said.

A minute later, she said, “So the people in Texas need a place to stay? They can get snacks if they’re hungry?”

“Sort of,” I said.

I thought that was that.

It wasn’t.

She explained shelters to her brother when he came home from school. He was intrigued.

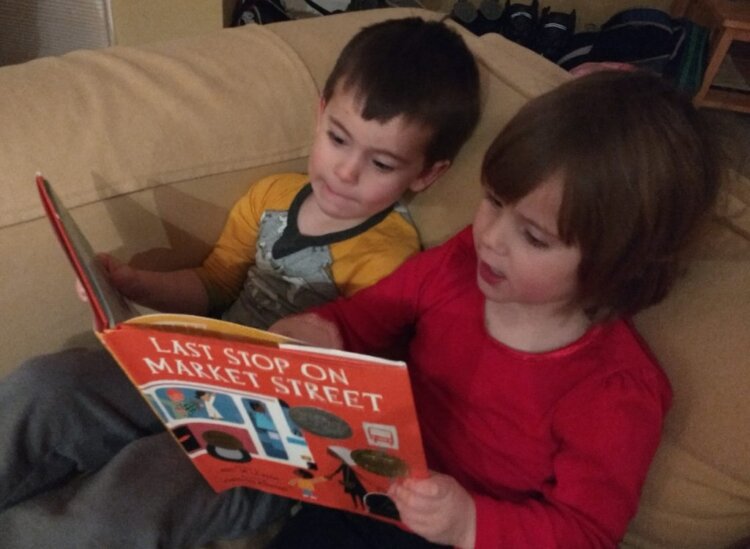

We read that book together every night for three months. They had daily check-ins with me about the people in shelters in Texas, and then Florida, and then Puerto Rico.

They wanted to know if they were OK.

Then a funny thing happened: with each reading, they wanted to know more, and not just about devastating hurricanes, and not just about CJ, the little boy in the book.

Why didn’t CJ, the little boy, take a car to the soup kitchen with his Nana? How could the blind man on the bus feel music? How can people watch the world with their ears? Why is there writing on the buildings? Why is CJ happy to be at the soup kitchen when he wanted to play with his friends?

We talked about poverty. Gratitude. Empathy. Blindness, which led to deafness, which led to a conversation about Daddy’s hearing aids. Making assumptions. How to ask questions. Manners. Subways. Buses. Taxis. Infrastructure. Severe weather in cities versus rural areas. Why we treat people with respect. Why we speak up. Why we don’t whine.

Each night, their understanding of the world grew a little deeper.

To my delight, they wanted to look for rainbows behind dirty buildings.

To my bigger delight, they wanted to travel to Texas to volunteer. They wept when I told them that they needed to be a little older, a little more independent. And yes, it was a children’s picture book that had nothing to do with hurricanes that helped me explain Hurricane Harvey—and deepened my kids’ understanding of humanity.

What makes a Good Book?

Three things: a clear conflict, relatable characters, and beautiful illustrations full of movement.

Even better? Rhyme or rhythm, pattern and repetition, and humor. If you don’t laugh, you’ll just cry. All the time. And that’s not productive.

What are some Good Books I can read to my kids?

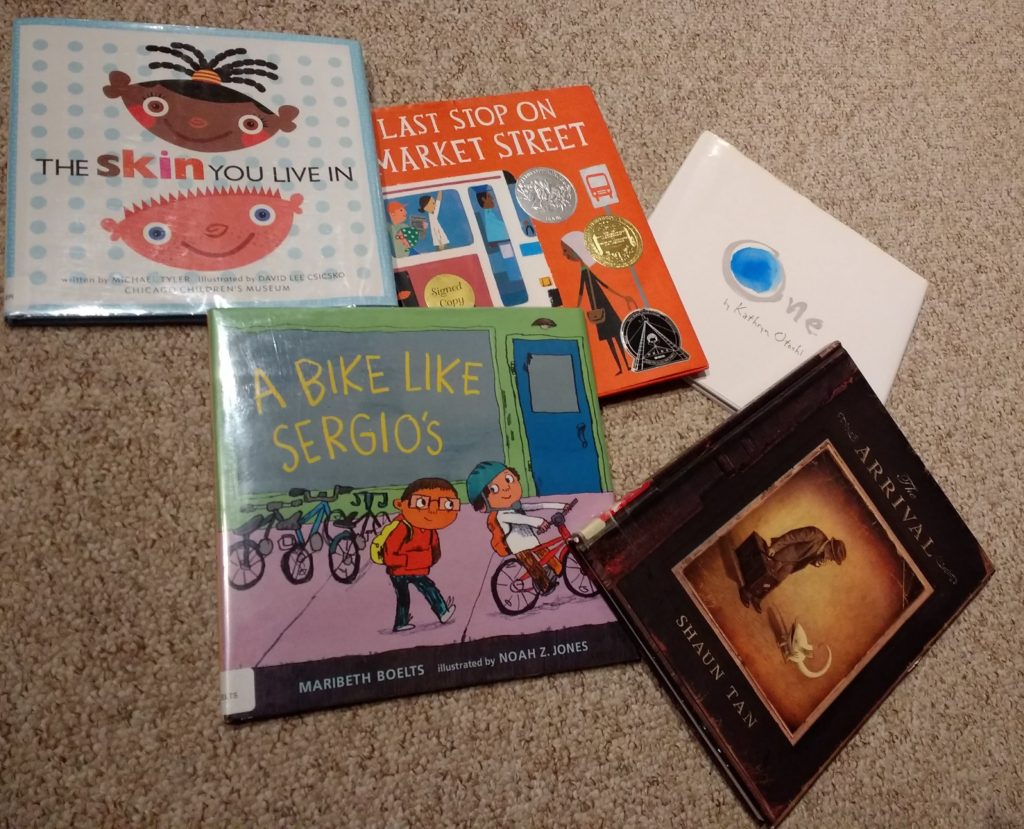

Christian Robinson’s illustrations of Matt de la Peña’s Last Stop on Market Street make a brilliant story come to life. I’m grateful to both of them for creating a dear favorite.

Similarly, Maribeth Boelts’s Those Shoes and A Bike Like Sergio’s give kids a way to understand poverty and how to make the right choices in a consumer-based culture, even when you’re a kid.

Our country’s racial reckoning is hard for some grown-ups to understand, let alone kids. The Skin You Live In by Michael Tyler, illustrated by David Lee Csicsko, and Julius Lester’s Let’s Talk About Race, are a good start. If you’re looking for a way to introduce why people look different from each other, and you’re ready to introduce the concept of identity, these books both do an excellent job.

I can’t say enough good things about Patricia Polacco’s award-winning work either, especially on issues of class, race, and gender, although some of the stories are a bit long for very young children.

When my 5-year old asked me what the word “immigration” meant, I found myself explaining how my great grandparents fled pogroms in eastern Europe at the turn of the last century. The conversation got a bit heavy.

I read the kids Shaun Tan’s dazzling graphic novel, The Arrival.

Here’s why I love it: there are no words! We looked at the book together and I heard my very young children tell me an immigration story. In their voices.

A lot of friends ask me how I talk to my kids about bullying. I don’t. I read them Kathryn Otoshi’s Zero and One, two stunning books that use numbers and colors as characters facing bullying, isolation, and fear, all of which they overcome with creative, honest solutions. My daughter has correctly identified certain political figures as “red” bullies.

I love Oliver Jeffers. His latest book, Here We Are: Notes for Living on Planet Earth gives little (and big) kids a breathtaking view of humanity from the perspective of outer space downward. It’s marvelous and funny—and it lets kids see that our planet is worth saving, not destroying.

There is a lot of bad news in the world. Give your kids a lifeline so that they can understand it without becoming undone.

Read to them. Talk to them. Let them ask the tough questions that they don’t know are tough yet. Be honest. Be patient. Be kind.

[Photo: The author’s children reading]

Alyssa Walker is a freelance writer and editor, parent, educator, and non-profit consultant. She’s interested in intersections: education, equity, the environment, technology, and politics. When she’s not reading or writing, she’s enjoys drinking good coffee, playing outside with her family, and cooking. She runs, hikes, bikes, paddles, skis, and lives in New Hampshire’s White Mountains.

Alyssa Walker is a freelance writer and editor, parent, educator, and non-profit consultant. She’s interested in intersections: education, equity, the environment, technology, and politics. When she’s not reading or writing, she’s enjoys drinking good coffee, playing outside with her family, and cooking. She runs, hikes, bikes, paddles, skis, and lives in New Hampshire’s White Mountains.

Grok Nation Comment Policy

We welcome thoughtful, grokky comments—keep your negativity and spam to yourself. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.