For people who have relationships with their blood family, it’s a given—and a gift—that they get to experience which biological traits they share: who they look like, who they sound like, and what traits and characteristics and talents they may have inherited. But as someone who was in the foster care system from birth until age 3 and a half (and was adopted at 4), I never knew.

Did I look like my biological parents? Did we have similar talents, similar skills? Did my voice sound like them? Could it be that an aptitude and love for music and art were inherited too?

I didn’t have any answers, only my intuition, and the guidance of my adoptive parents to nurture my instincts, talents, desire to succeed and my drive to survive. Yet, despite not knowing who my biological family was, I knew enough to know it was a blessing that I was alive.

Early life

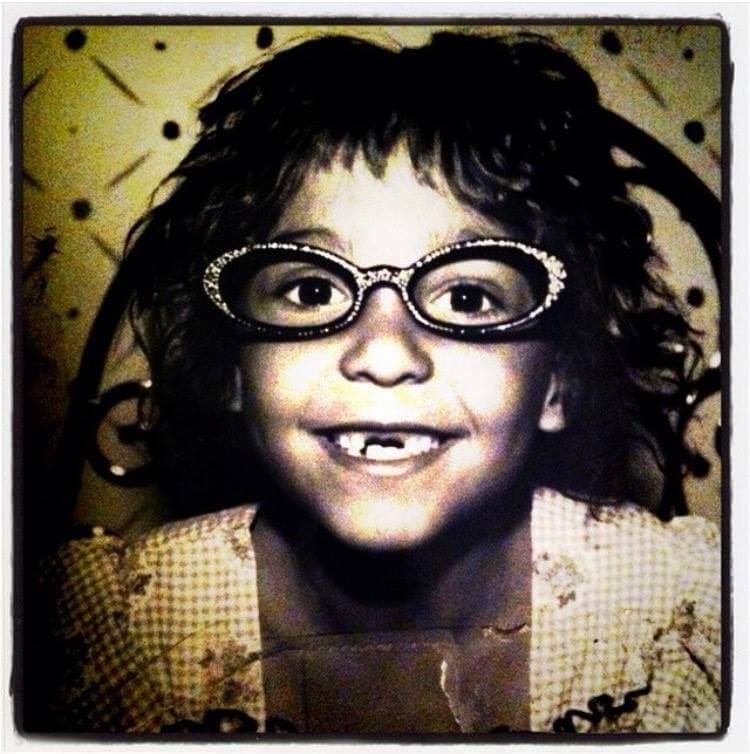

Cami-baby. On the day I was born—I was later told—for my safety and well-being, the police placed me into the first of what would be four foster homes: The reason that I rotated through them was that the police had discovered that I was being exposed to danger in one of the homes, so they moved me into an emergency short-term home, and shortly thereafter, into a final home, bringing me together with the family that permanently adopted me. By specific request from my biological mother’s side, I had been placed with a wonderful, stable Jewish family: similar in Jewish culture and values to my biological mother’s side.

From the moment I arrived into what would become my permanent home, the survival skills I had gained in foster homes (namely an ability to charm and play music) allowed me to better adapt. This home came with two stable, understanding parents to guide me, three older brothers, one of whom lived at home with me before he left for college, and two of whom visited on weekends. And I had a piano for a best friend.

At 4, I was old enough to understand that I had been in foster homes; and in the process of being adopted, I had been told bits and pieces of my biological parents’ story, but most of the details were kept from me until I was a teenager. Looking back on my childhood, I don’t recall identifying too strongly with negativity or a sense of sadness; I was an optimistic child. I always had an interest in my biological roots, but I was strongly advised to focus on my current life rather than to delve into any past.

My adoptive parents, siblings and extended family made sure that I understood that I was loved and wanted. They enabled me to discover my tools and talents and taught me self-reliance, for which I am forever grateful. When I was adopted, I couldn’t yet read, write, or identify letters, colors, and numbers, so my adoptive parents hired tutors to help me with my education. They fostered my love for music, composition, singing, writing songs, acting, and movement by enrolling me in various classes to help further develop my talents. My artistic drive consumed a lot of my focus and my mind in healthy and positive ways throughout my childhood.

From time to time in my youth, however, I can recall feeling identity emptiness: wondering exactly where it was that I came from and what my entire biological lineage and cultural heritage was. I often wondered if my artistic skills were genetic since none of my adoptive family was musical at all, but I was also aware that this was something I might not ever get to know.

Teenage changes

When I was 17, my adoptive parents were informed by the state that my biological mother, Mary Lou, had died from an overdose. At that time, my adoptive father was ill with cancer, and my adoptive mother wanted to wait until I was 18 to tell me about Mary Lou, hoping I would be emotionally able to handle this information and its consequences. (My adoptive father died when I was 18.)

I was privileged to meet many of my biological mother’s side of the family and they have been good to me ever since. I always felt so fortunate to connect with my parts of my maternal side, which has deeply enriched and fulfilled a part of me. They urged me not to reach out to my biological father’s side of the family, but told me that my biological parents had not been in anything resembling a traditional relationship. I learned that my biological mother (who was Jewish) had conceived me in her 30s while my biological father (whose heritage stemmed back to England then later Tennessee and Texas) was just 16: They were surrounded by a life of drugs, crime, and both struggled with mental wellness challenges. For my safety, I was put up for adoption, despite the fact that they had never really wanted that.

How music shaped me

Because I struggled with some aspects of traditional learning in school, I had planned to go to New York to live the life of a performer upon completing high school, but thanks to my adoptive parents’ urging, I was admitted at UCLA as the first jazz vocalist in Kenny Burrell’s new four-year jazz program.

In my 20s and 30s, I discovered ways to market, brand, and sell my music, performing all over Los Angeles, the country and ultimately in over 14 countries around the world with a backpack full of my CDs, my guitar, and the charm and social skills to maintain friends and contacts in each given city in order to return again and again while building a loyal fan base for my music.

I have been supporting myself through licensing my music, the sales of my CDs, teaching music, English writing, and Jewish studies, excelling specifically in Jewish music education and aiding students in areas of special needs and learning disabilities. It is also true about me that my moods can sometimes be overpowering and overwhelming for myself and others when communication breakdowns happen, but I am content with my relationships and friendships and I have always considered life to be a wonderful gift despite its challenges.

A shift in perspective

In September 2015, I read an article online about how to heal your life in areas you may not even know needed healing in order to prepare to have a family of your own. This was the main turning point that inspired me to reach out to a private investigator to see if any of my paternal biological relatives were still living. Given my awareness of the drug addiction, criminal history, and mental wellness challenges connected to my biological family history, I approached with caution.

The PI’s research (which I believe my heart intended for me to find) led to a phone call with my biological grandmother. I was finally able to ask the question I had been wondering for so long: “Is my biological father still alive?”

Her answer was yes. A breath escaped my lips and I hung up the phone, never intending to call again.

A few weeks later, I decided on a whim to drive past the address where the PI’s research revealed that my paternal relatives resided. I still was very hesitant to open a door to a part of my story that so many people were urging me to keep locked; I drove and stopped out front, but didn’t actually approach the house.

Over the next few months, I occasionally wondered how the people in that house were doing, and moreover, who in fact were they really. One morning, I felt a deep nagging inside of me: the thought “you must call that number” would not leave my mind. For a few hours, I called and called but to no avail; no one answered. I’ve always been a very intuitive person and something about her not picking up felt wrong to me. I searched through the legal documents I had obtained from the PI to find another phone number and I called it.

The person who answered told me that my biological grandmother—who I had spoken to just months before—had passed away, but that my biological father (who will be referred to as ‘D’ in the rest of the series), Uncle Jimmy, and a half-aunt, nephew, and half-uncle were still alive. I was told that they were all “unwell” and still embroiled in legal issues involving crime and drugs.

That phone call could easily have been an indication to walk away from all of this, but I felt that I must go see it for myself. I got on the Metro the very next day with nothing but a house key and identification; I got off the Metro at the exit that would take me to where they lived.

Connecting with Uncle Jimmy

I walked up to the house and there was a man outside cleaning. From a distance, I couldn’t quite see his face. Could this be D? Or maybe it was my Uncle Jimmy? I thought to myself, “Is he dangerous?” I decided that criminals can’t be immediately dangerous and threatening if they are in the middle of cleaning up, so I approached. He glanced my way briefly, then returned to his task.

I asked softly, “Are you D?”

“No; what do you want?”

“So would that make you Jimmy?” This made him stop in his tracks. He looked up at me, but I could tell he hadn’t figured out who I was.

I realized that I was about to enter into all of my biological family’s lives without permission. So I asked, “How would D feel if he were to meet a family member of his?”

Jimmy replied, “What do you mean? What kind of family member? We know everybody in our family…” His voice trailed off and he squinted his eyes so he could look at me a bit closer.

Before he could say anything more, I said, “Well… yes, but do you think that D would be OK with… I mean how would he feel about.. you know, I just mean… would he be OK with the idea of meeting his biological daughter?”

Jimmy didn’t miss a beat. He said to me, “Wow—you’re Mary Lou’s kid?! Come in, come in!”

And I did come in: deep in this dark dwelling was a small space for the living just beyond the dead. Hidden in the darkest of darkness of this hallway were 24 sets of cat eyes, stacks of music everywhere, and music posters and drapery along the wall. The drapery and a collection of crates separated the hallway into two makeshift bedrooms.

As I waited for D to arrive, I listened to Jimmy’s stories for hours, quickly discovering his musical talents and that he—like me—was left-handed. I learned that my biological father was also an excellent musician. Living as a musician, I had always suspected that my talents were in some part a biological inheritance: Now I realized that they probably were!

Jimmy told me some stories about his and D’s childhood, constantly assessing my intellect, awareness, and understanding (I later discovered he had left out certain harsher details of my biological father’s past that he wasn’t sure I was ready for). I found his concern and care for me particularly touching. But during this first visit, D never showed up.

I returned to visit with Uncle Jimmy a second time, offering him some more information about what I knew about my biological family. I was trying to encourage him to open up to see if his stories matched what I had been told by the PI and the legal documents I had seen. They did. This established our first line of trust. A deep bond began to form between us. But much as I enjoyed this time with Jimmy, I had come to find D, and he was nowhere to be found.

I learned that my father was very much a free spirit; in love with the freedom of the outdoors; this was a deep contrast to much of the rest of his life, his incarceration for petty and grand theft, as well as numerous drug-related crimes. For D, living in the bushes between casinos or on the streets meant that he could double his welfare money and take his drugs in privacy. He later told me that he equated this freedom with the most incredible peace of mind he had ever known.

On my third visit, Uncle Jimmy had new information for me. “D is in the back. He is passed out sleeping, but soon you will in fact meet your biological father.”

I couldn’t believe it. I was nervous and excited. I was ready.

Read the next post from Jenni/Cami, where she tells the story of her first encounter with her biological father.

Listen to her song “Heaven,” which Jenni wrote about foster homes and being adopted. You can download the song for free on Soundcloud.

Grok Nation Comment Policy

We welcome thoughtful, grokky comments—keep your negativity and spam to yourself. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.