Take My Nose, Please is a documentary by a self-identified lover of plastic surgery, journalist Joan Kron. Joan takes us behind the scenes of two women’s journeys towards “beautifying” their faces through plastic surgery.

Emily Askin is a very funny and striking comedienne. She has a lot of confidence, a terrific smile (with gorgeous teeth) and a sharp and bold nose which I think is perfectly fine. Emily is engaged to a man who loves her face and her nose, but says she should do whatever makes her happy. She sees making her nose “smaller and higher” as an act of self-love. As a survivor of sexual abuse and as someone who has struggled with her weight and body image, plastic surgery feels empowering to her. “Why not have the nose you want?’” she asks somewhat rhetorically throughout the film.

Jackie Hoffman is a successful and immensely talented comedienne who has made a career out of self-deprecating musical comedy numbers about plastic surgery, among other things. She has a very unusual face and thinks she is terribly ugly. Jackie is more skeptical about surgery and feels it’s an act of self-loathing, not self-loving. She has a stable and seemingly loving husband who loves her just the way she is. She ends up getting a nose job and face lift.

The documentary follows these two women to doctor’s appointments and we get to see dramatic before and after shots. We also meet a few plastic surgeons along the way, as well as academics who explain the history and significance of plastic surgery. All of them admit at the end of the film that they have had plastic surgery, by the way.

Watching this documentary made me consider going back to school for a doctorate in women’s studies with an emphasis on body politics. And it brought up some painful feelings.

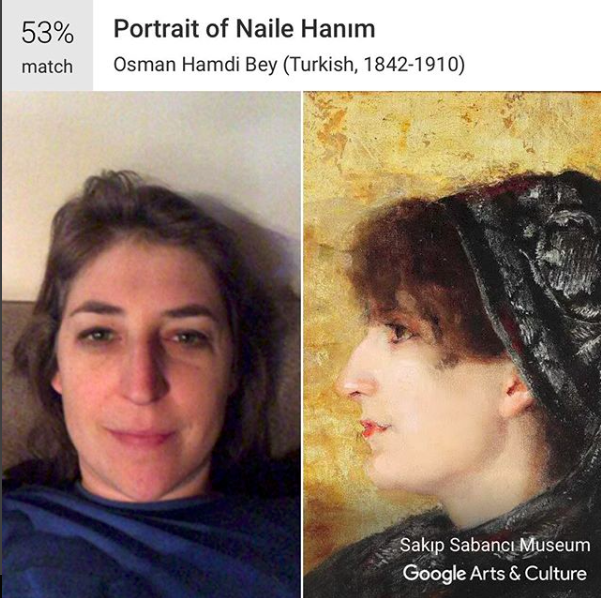

Of course, I couldn’t help but think about my nose when I watched this. I’ve had a prominent nose pretty much since I was 10. My brother and I have the most prominent noses in the family. As a young girl and teenager, I would cringe when I overheard relatives of mine criticizing ‘big-nosed’ actresses. It’s a source of pain for me and always will be.

My parents raised me with pictures of Bette Midler and Barbra Streisand practically inside of my school lockers, so I would see that women who “looked like me” could have exciting and successful careers. When I got the opportunity to work with Bette Midler at 12 in Beaches, I finally saw what my parents meant: she totally looked like me, but with red hair and brown eyes. And I looked up to her so much not just for her talent, but because she made me believe that women who looked “like us” could be successful and valued as actors and comediennes.

I think back to the hours I spent looking into the mirror while holding a second small mirror up to my face as a teenager. I examined the bump in my nose and tried to remind myself I was beautiful, but I rarely saw women who looked like me celebrated as beautiful. Boys teased me, girls teased me. So many Jewish girls I knew – and many non-Jewish ones as well – got nose jobs, and while I wished they would love themselves as they were, I secretly envied their perky adorable noses. No one would ever describe my nose that way.

I remember someone once told me that if you get a nose job, you also need to get a chin job if you have a face like mine. Because my prominent chin actually balances out my nose somewhat. So I was basically looking down the barrel of two surgeries if I even dared contemplate one!

When I decided to wear my hair parted in the middle in high school to complete my ‘hippie chick’ look, I loved looking like so many women I saw in photos from Woodstock. But after I made the switch to parting it on the side again, my brother told me the middle part had drawn too much attention to my nose. I still keep it parted on the side and any time I play with parting it in the middle, I just see a mistake.

I learned something from this documentary that I now am obsessing over. Emily was ‘diagnosed’ as having a nose that ‘drops’ when she smiles. It’s apparently a sort of criteria for a nose being “too big” for one’s face that when you smile, the tip of your nose kind of dips down. As this woman’s nose dropped in her ‘before’ images, my heart dropped. That happens to me. I never knew it was a “thing.” I just know that in many pictures, I get really upset when I’m smiling and the tip of my nose has dropped down. And now I feel like it’s a thing I’m focusing on. Because I am.

I considered plastic surgery many times, especially after certain TV critics insulted my nose when I was on Blossom. When SNL spoofed Blossom, they used a large, hideous prosthetic nose on the actress who played me. It hurts being publicly ridiculed for your features. If I had gotten plastic surgery, it would have been because I hated my nose. And my chin. It would not be an act of empowerment or beautification. I am in the minority in LA and in my industry because my face is untouched, as is my neck. I don’t dye my hair and I don’t plan to change these things.

Sometimes I wish I didn’t think so much and could just say, Why not make me the best version of me that I can be? And then I remember what Lady Bird says to her mother when her mom says that: “What if this is the best version of me?” What if changing this wrinkle here and that age spot there would just be trying to doctor a deeper self-image conflict? Then what? Where would it stop?

We learn from the film that plastic surgery was pioneered by a female surgeon in the late 19th century. With so many men out of the workforce because of WWI, women had to take factory jobs and office jobs in record numbers. The highest paying jobs were also the ones where ageism was strongest, as was misogyny. This surgeon believed that if women could look younger, it would increase the probability of them getting hired and staying employed in an uncertain economic climate and world. And she was right.

This ageism, misogyny, and secrecy surrounding these procedures has persisted into the 21st century. Women now go to greater and greater lengths to look like the airbrushed images we see in the media. We are competing with women who are professional models and fitness trainers. We are trying to erase the signs of aging because young is attractive and women become disposable after they start to look 40.

Even Emily, who had claimed the surgery was an act of self-love, breaks down when her fiance doesn’t react as dramatically as she hoped he would – she loves her new nose, but he is nonplussed. Because he loved her before. So is it about self-love? Or is about acceptance by others? Specifically: is this about pleasing the male standards of beauty we have internalized as our own?

The comedy of Phyllis Diller, Fanny Brice (the first woman to publicly discuss plastic surgery for her distinctive nose in the early 1900s), Joan Rivers, and Totie Fields (who had to have a leg amputated after a botched plastic surgery in the 1970s and who died the following year) is interspersed throughout the documentary. Women’s honesty about plastic surgery is reserved for comediennes, it seems.

The plastic surgeons interviewed – all of whom are tight faced men in their 70s – discuss the differences between people who want to perfect themselves and people who want to fix something inside of them. They cite Joan Rivers and Michael Jackson as those searching for the latter. They claim to want to ‘avoid’ those patients, yet there are so many surgeons who take on clients with nothing really wrong with their faces except that they want to change them.

Ultimately, I wish every woman loved herself as she is. I wish all women with grey hair would stop dying their hair. I wish everyone would cease injecting their lips and their eyes and their “expression marks” and “laugh lines” with botulism. We are all beautiful because we are all human. And we age. It’s normal. And when you go to countries where plastic surgery is less common, the emphasis is not on aesthetics and appearance. It’s about what’s underneath.

At the same time, I wish I understood this aspect of female culture, because I feel left out. And people say things like, “You’ll understand soon and you’ll do it, too.” Or they say, “Well, you’ve already made an identity for yourself as an ethnic actress.” Or they’ll say, “Jennifer Grey changed her nose and she never worked again!”

And so I recommend this documentary for anyone curious about plastic surgery, anyone curious about self-love versus self-loathing, and anyone interested in the fascinating conversation female comediennes in particular have about their faces and their beauty. Much of this kind of comedy appeals to men’s sensibilities – as Phyllis Diller put it, it was about saying we are ugly before they can- and much of it appeals to our own notions of what is beautiful, what is acceptable, and what needs expensive and in many cases dangerous procedures to make acceptable.

Read More From Mayim

Read More From Mayim

Grok Nation Comment Policy

We welcome thoughtful, grokky comments—keep your negativity and spam to yourself. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.