A toxic and heartbreaking relationship had ended, life-changing acting success was in my grasp. Me? I just felt lingering uncertainty about the course of my life. The dreaded “what’s it all about?” query had me reeling. Everywhere I seemed to look held nothing but mundane indifference. So, I did the one thing everyone does at this crossroads….I became a lumberjack. Right? What? So, just me then?

I moved to Los Angeles from a small town in Oklahoma to follow my acting passion. I spent 14 years bartending, waiting tables, taking acting classes, struggling, experiencing poverty all to follow my dream. A major relationship ended, breaking my heart, but my professional life was soaring. At 42, I had booked a few great roles in interesting, “big” films, with people I had always wanted to work with. I filmed a major network pilot, and a few episodes here and there on TV shows. But once I had “arrived” and was on the ledge looking over my dream come true, I was sitting at a read-through of a script for a show and I found myself feeling empty and a little depressed. I wondered “Is this it?” It was unnerving; professionally everything seemed awesome but personally, something felt off.

As it often is with this business, it all came crashing down over the course of two weeks: one movie fell through while another was scrapped due to the divorce of the film’s producers; the TV pilot I shot was horrible, and didn’t get picked up. TV work dried up. And it happened comically fast: one minute I was Ryan Downey Jr. Gosling Day Lewis DeNiro Renner, the next minute I was back to being Jeff looking for another service industry job.

This, on the heels of the break-up, sent me into a very reflective and thoughtful self-examination: I immersed myself in nature, meditation, retreats, walks and hikes, trying to get lost and found in nature, just outside of Los Angeles, and beyond. I took day trips to camp in the outdoors: backpacking all day, simplifying and scraping away city life. Pretty soon I made it a habit to climb a tree once a week just to see if I could do it, working very hard to get up there, then remembering at the top that I had no idea how to get down, and eventually just jumping. After a few sprained ankles and scraped elbows and knees, I started to feel energized. The basics came back to me: a boy. A tree. A mini adventure like the ones I had countless times as a child.

It became more and more pressing to me to get away from Los Angeles to be in my beloved outdoors. As a person who tends to think in extremes, it couldn’t just be a tree-covered hill; it had to be a mountainous sanctuary! I had long idealized the thought of a cabin in the woods; a stark, simple existence; growing a large beard and never being seen by anyone except when I strolled into the general store to get supplies; a sort of getting back to me (whoever the hell that was) and disappearing.

After pondering my imaginary secluded mountain life for what seemed like years, I found myself talking to a family friend about life and waxing poetic about the future and the emptiness I was feeling. I realized that I was essentially unskilled; that I literally hadn’t learned anything new in 20 years. I didn’t know about anything but acting.

Around this time I had seen “Wolverine” and seeing Hugh Jackman looking all rugged and hiding out from the world as a lumberjack reminded me how, at 15 or 16, I had seen amazing historical photos of lumberjacks. They felled entire forests of colossal trees, clearing space for all of our roads, bridges, and highways. I remember old videos of them rolling the trees down to the river, hundreds at a time, as a guy with a long pole with a hook on it nimbly pranced across these rolling logs, wrangling them. I remember being impressed with these men, that life, and that world.

One day, I blurted out, “Jesus, I just want to live in a cabin away from everything, grow the biggest beard, and be a fucking lumberjack.” My friend said “If you really want to be a lumberjack, I have a connection.” That sentence sent a jolt of fear and wonder through me. At that moment I knew for sure that – even though it meant leaving my dream career, and even though being a lumberjack was dangerous – I was going to do it.

I moved to Oregon to begin three months of lumberjack training. I was up at dawn – a time when the sky and horizon is just about as beautiful as you can imagine. I worked out in the morning and was at the station to catch the “crummy,” a truck that drives you to the work site. On-site shifts are sometimes for 8-10 days, working until the sun goes down.

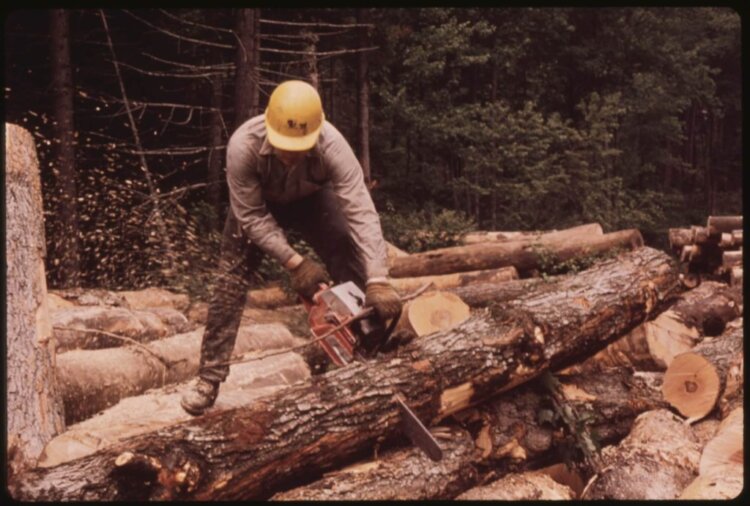

At first I did odd jobs: lifting things from here to there, removing messes, and staying out of everyone’s way. I would often work the loading dock, unhooking large chains from logs; as they rolled by, I would take a little saw and take off the knobbys, a process called “bucking,” to smooth out the trees to make them easier to transport. I would end the day with sawdust in places I didn’t think possible and my face was so dirty you could only see the whites of my eyes. The guys taught me how to cut a tree down in a way that it would fall within inches of where you wanted it to go.

After four months of this, I was moved to what they call the “war zone,” where you are chasing trees that are hooked up to large cranes, making sure that they don’t hit anything (including you); and “choking,” racing across stacks of logs to hook a chain to a tree that needs to be pulled out of deep canyons and valleys. It’s pure danger and adrenaline and I’ve never been so scared and thrilled in my entire life, aware that my life could end any moment. I don’t consider myself overly brave or daring, but something about this job appealed to me in the most philosophically and purely physical way.

Next, I was allowed to be a high climber: a lumberjack who uses a rigging to climb to the uppermost portion of the tree and take the top off. This allows the tree to fall safely and keeps the trees in manageable logs for easier removal and transport. When you cut off the top of a tree, the tree sways and you sway with it in what feels like ten yards in either direction; you feel small and puny… talk about humility!

I shifted between these three jobs and the odd jobs for about 15 months, working 8-12 hours a day. We had a few breaks, and a lunch break. I remain in awe of the work ethic of my coworkers.

Aside from work, I mostly existed in solitude. I had my own cabin in the woods for the first six months. I didn’t have too many friends. I’d have a few friendly chats around town occasionally with the grocer, but the men and few women I worked with mostly had spouses and children to get home to. Other than a few beers after work on the rarest occasion, I didn’t socialize.

On the job, I felt real kinship and trust and respect. We laughed a lot, joked a lot like any other job, but something was electric about it for me – it felt like I was creating my own rite of passage. Still, I think the crew sensed that I was not in this for the long haul. And for the duration of my time as a lumberjack, not one person on my crew knew I had once been an actor.

About 18 months in, one rainy day, I was up on a tree and I had just taken the top off. The tree swayed a bit more than usual and I started to edge down slowly when my harness broke. I fell; hitting stray branches on the 40-foot drop. I grabbed branches to try to slow my fall, but then there was nothing left to grab and I plummeted the last twenty feet, slamming into the fallen trees and rocks and debris below. I was instantly knocked unconscious. I broke three ribs, dislocated my shoulder, gashed my head, and tore up my knee. Because we weren’t near any sort of medical facility, they had to fly me out by helicopter. I don’t remember anything except waking up in the hospital bandaged up and in extreme pain. I was very lucky; a few feet to the right and I would have toppled down a cliff; a few feet to the left and I would have smashed onto a collection of boulders.

I was in the hospital for a week or so, and recovered for a month. I decided to not resume my lumberjacking duties; it’s not something a man can realistically pursue as a career at 43. The experience had been everything I had hoped for and more; but I had begun wondering if, now, acting might be the right thing for me. After a few odd jobs and a bit of travel, I moved back to LA.

On reflection, I realized that – in addition to learning new skills – I had also learned a lot about life:

- The scenery is incredible. Rivers, trees, mountains. For the first time, I knew what it meant when people called it “God’s country.” Now, whether you’re in the city or the country, I highly recommend as often as you can. Don’t let life become just a view or a backdrop.

- The job required me to be in the moment, living solely in the present. There is something so amazing about a job that requires you to be in present time. There is a plan, but in terms of implementation, you have to think moment to moment. A foothold, a cut, linking a chain that has to be secure or else. You are right here right now all the time. Pay attention to what IS, everything will come in its time.

- I learned how much I was physically capable of. Knowing what you are capable of when you have to be capable of it is a pretty amazing experience.It was the most rigorous and vigorous work I had ever done, beyond anything I thought possible. There is a wonderful discovery when you find hidden depths and the ability to “dig deep” just in order to get through the day. Every night I went to bed drained and profoundly sore, and every morning I woke wondering how I would do it again. Then…you do.

- The experience opened me and helped me understand brotherhood. While I had expected the experience might “make me a real man,” the single most surprising thing about my life as a lumberjack was that it softened me; it opened me because of the people I was around. I expected to be around grizzled, hard-as-nails men of the frontier and the women who loved them. And I was, but these people also had astounding care and sensitivity. They really have each others’ backs, not only because they have to or people can get hurt, but because they believe in what they are doing and in each other. They are tough, but not hard, strong, but not inflexible. I’ve never been to war, but when I hear soldiers talk about brotherhood, I understand it as much as I possibly can because of this experience, which finally taught me what “being a real man“ truly meant. I also learned that while the brotherhood is wonderful, staying in a trailer with ten guys who haven’t showered all that much for ten or so days isn’t that much fun.

- A life in the woods requires abundant bug spray. BUGS! You get eaten alive. I think I own shares in “OFF” bug spray.

- I don’t sweat the small stuff as much. Yes, I still sweat the small stuff sometimes, but I am profoundly aware that it is small, trivial stuff. The Romans practiced what they call “memento mori“ (“remember you are going to die”). After having looked death in the face a few times during my adventure, I don’t fight things as much. I don’t spiral downward as much. I learned that you can have all of these wonderful thoughts in your head and self-discoveries on your own, but sooner or later, you have to collide with life. Staying true to that sense of being while butting heads with the ups and downs of life is really the key. If there is a key….

- To do this amazingly difficult job, the one thing that has to be present is an absolute vulnerability. The places you are working in are breathtakingly beautiful, yet held great peril around every corner. You have no choice but to acknowledge that you are on nature’s terms and not yours. Respect for Mother Nature easily trickles into respect for the person across from you risking their life to do the same thing. Once I was very close to breaking apart emotionally after a bunch of rough days and the foreman (who literally was hard as steel) came up to me, and very gently said “Hey it’s ok; we all go through it. Let it happen.” This was astonishing; he absolutely acknowledged the need to be human and sensitive even though he was so tough.

- In addition to learning new skills, I also learned what it was to let go. I learned to let go of an identity that has been constructed for years and years, and just be. Nothing added, nothing taken away, nothing to gain or lose, just a real sense of being myself, as is.

These lessons became part of my life upon returning to Los Angeles and to acting. I left lumberjacking three years ago, but it still affects everything.

Jeff Kerr McGivney is an actor, writer, teacher, and adventurer. He is based In Los Angeles and is currently sailing the ocean blue in Key West, Florida.

Jeff Kerr McGivney is an actor, writer, teacher, and adventurer. He is based In Los Angeles and is currently sailing the ocean blue in Key West, Florida.

Grok Nation Comment Policy

We welcome thoughtful, grokky comments—keep your negativity and spam to yourself. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.