I was sweating through my first (and so far, only) visit to the trendy SoulCycle studio in Beverly Hills, where young people gather for what the website calls “joyful fitness.” I was intrigued by the hype, and an invitation from one of my sweet students to try it out with her. What’s more, the journey at SoulCycle promised to “break through boundaries.”

To my great surprise, I did break through boundaries. Beyond the physical exertion, there was an emotional element. As I listened to the words of the instructor and the words of the music, I found myself absorbed in thought. The year had been particularly difficult for me. My father had died, my mother struggled with the meaning of her life in his absence, and all this was taking a toll on me, my husband, and our three young sons.

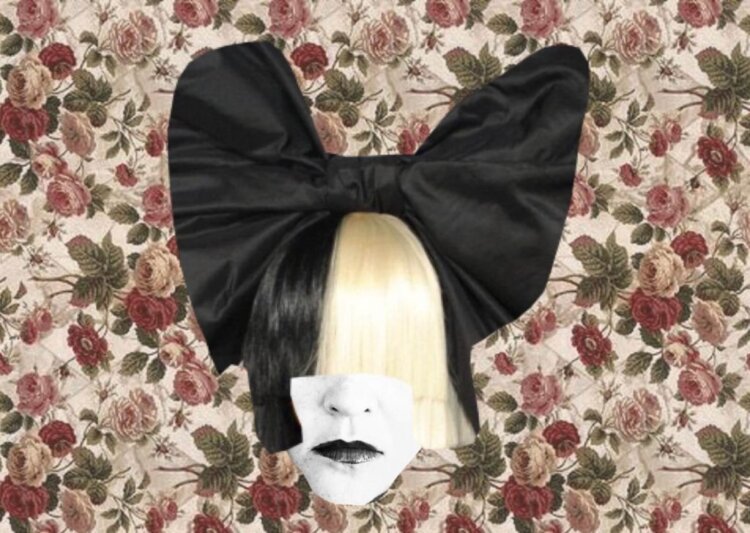

During the class, my mind caught hold of the lyrics in one of the songs, Sia’s “Bird Set Free”: “I don’t wanna die, I don’t wanna die.” Besides not wanting to die there on the bicycle from this crazy workout, something deep inside me was stirred by the message of this song; you might say, my soul was aroused by this visit to SoulCycle. Thankfully, no one noticed my tears in the darkness.

Even after my immediate visceral reaction in class, the song continued to resonate. Because of my background as a Jewish educator, I can’t help but see the world through a Jewish lens. A few months ago, Adele’s “Hello” seized my imagination; I adapted that song’s melody and themes to words from the Mourner’s Kaddish, recited by mourners as affirmation of belief in a time of grief. (That song now has over 195,000 views. ) This time, the lyrics of Sia’s intense and challenging song began to move me into the themes of the High Holidays. At this season in the Jewish cycle, we reflect on life and death, beginning our new year with prayers to be written and sealed in the Book of Life: “I don’t wanna die, I don’t wanna die…”

During the High Holidays, the services of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur reach a climax with a stunning vision of heavenly judgment in a prayer called Unetaneh Tokef. “Let us give voice to the power of the holiness of this day,” is my translation of the opening words. We give voice to this power by describing the heavenly court, in which each earthly soul passes before God for judgment. This central moment in the service is always a source of theological and existential questioning for me. How does God reckon these judgments? Why does it seem like good people are dying while evil flourishes? At the end of the day, do our good deeds really matter? And this year, I will be raising more personal questions: Why do fathers have to die? How will a wife keep living without her life’s partner? Why can’t grandchildren grow up to know their wonderful grandfather, their Zayde?

The Unetaneh Tokef provides no conclusions, only asking “Who shall live and who shall die?” I wondered: What would happen if the words of this ancient prayer were woven into the tune of Sia’s “Bird Set Free”? With this thought, new music for my Jewish soul’s cycle was born: the Sia Unetaneh Tokef.

As the project took form, my own voice became stronger. The opening lyric in the original Sia song states, “Had a voice, but I could not sing.” In my version, I do have a voice, and I most certainly can sing. I sing out proud and strong, for the purpose of prayer and spiritual fulfillment, asking to be a partner with God in the process (“Adonai, sefatai tiftach – God, open my mouth,” words from the a central Jewish prayer known as the Amidah). For some listeners, my voice and interpretation of the sacred prayers has been disturbing, even sacrilegious. As a traditional Jew, posting a video of myself singing challenges the taboo of “kol isha,” the Jewish idea of keeping women’s voices private.

The voices, experiences, and perspectives of women have traditionally taken a back-seat in Judaism. Likewise, the metaphors used to describe God in the liturgy are usually masculine. In Judaism, while God is neither male nor female, we frequently refer to God as our “Father” or “King” in the High Holiday prayers, and these have important connotations of God as divine judge and master. However, while working on this song, I felt it was appropriate to emphasize a feminine quality in God’s more hidden voice, the “still small voice” from the liturgy, which “tells us she is near, keeping us alive, keeping us alive.” I had a deep desire to call out to God through the female pronoun, drawing connotations to the qualities of mercy and forgiveness we seek on this holy day.

In the background of all this life and death drama in the themes and liturgy of the High Holidays, the sound of the shofar 100 times during the Rosh Hashanah service and the solitary long note at the end of the Yom Kippur service announces God’s presence. The ancient musical instrument made of a ram’s horn erupts, both in the prayers of the High Holidays and in the background of my song. The shofar arouses the soul to repentance, giving voice to the wordless cry we feel in our awesome encounter with the divine.

This year, the music of this project has given words to my wordless prayers. My soul has travelled a meaningful cycle of ups and downs, riding beside others who share in the tears and sweat of the journey. Together, we are always listening for the right phrase or tune to help us break through our boundaries, through our despair and pain, hoping to continue living fully, amidst both tears and joy, in the new year ahead.

Nili Isenberg is a middle school teacher of Judaic Studies, making ancient texts and practices relevant to a new generation at Pressman Academy in Los Angeles. Nili also devotes time to making Jewish learning, prayer, and ritual meaningful in her personal life.

Nili Isenberg is a middle school teacher of Judaic Studies, making ancient texts and practices relevant to a new generation at Pressman Academy in Los Angeles. Nili also devotes time to making Jewish learning, prayer, and ritual meaningful in her personal life.

Grok Nation Comment Policy

We welcome thoughtful, grokky comments—keep your negativity and spam to yourself. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.