Marine biologist Silvia Earle said, “For humans, the Arctic is a harshly inhospitable place, but the conditions there are precisely what polar bears require to survive – and thrive. ‘Harsh’ to us is ‘home’ for them. Take away the ice and snow, increase the temperature by even a little, and the realm that makes their lives possible literally melts away.”

By this definition, I am more like the polar bear than the human. I was raised in Kotzebue, a town of just over 3,000 people located in Northwest Alaska, about 30 miles above the Arctic Circle. My people are referred to as “Eskimo,” a controversial term coined by colonizers to describe many different cultures in the North. We are Inupiaq. Since time immemorial, the Inupiat have lived off this land, hunting for food for survival, and like the polar bears, we too thrived in our own self-sustainable ways. We did not have cars, we did not waste resources, and we did not have plastics to dispose of. We did not create waste other than what came from our bodies.

Currently, the Arctic is warming twice as fast as any other region in the world. The people that live here, like the polar bears, are experiencing it in our day-to-day lives. This year alone, I have witnessed multiple landslides. In one of them, I stood watching as the ground melted and ran into the ocean. For me, it was a reminder of the land that is changing, of my home that is literally melting away.

Many rural Alaskan communities like mine depend on subsistence (hunting and gathering from the surrounding land) to feed their families. In Kotzebue, we can’t afford to buy products at the grocery store: for example, a gallon of milk is currently $9. We depend on the caribou that migrate through, the berries that grow on the tundra, and the fish that swim up river. Now, caribou populations are in decline and their migration patterns are constantly changing due to a number of reasons, including warmer weather. As the tundra warms up, and the permafrost melts, new species grow, causing changes to our berries. The fish are directly impacted by ocean acidification caused by warming sea temperatures. Typically, the ocean freezes up by late September. This year, at the end of October, the water was still completely open and finally started freezing up over a week into November. All these changes have huge impact on our way of life.

As we struggle to figure out what is going on with the land, we are also losing some aspects of our culture with it. Our elders try to teach youth values and traditions, many of which are taught through subsistence hunting and reading the land by surveying one’s surroundings. But how do you teach someone how to hunt and how to read the land when the land is changing and you are trying to figure it out for yourself? This loss of culture contributes highly to the decline in mental health in Arctic communities by taking away our identity. Treatment is rare, as we don’t always have a counselor in town, or the funds necessary to go somewhere else to get help.

These points of impact are caused, on a large scale, by actions that happen very far from the Arctic. Carbon emissions are the lead contributor to climate change (one example of man-made carbon emissions is car use). To address high carbon emissions, the United States and 192 other countries signed the Paris Agreement that officially went into effect on November 3 and calls for the decrease of use of fossil fuels and that these countries begin transitioning to renewable energy sources. If the United States sticks with this agreement, it will help, but I don’t believe it will be enough.

Since 2015, when the United States became Chair of the Arctic Council, the federal government has put a lot of focus on climate change and its effects on the Arctic. Campaigns have provided more public awareness of impacts on the environment and people. Funding is starting to go towards finding solutions to mitigate and adapt as well as addressing infrastructure needs, especially in more rural areas.

We all need to be more accountable, especially on an individual level. All of us can use our vehicles less. We can use less plastic, and if we work together, we can urge companies to stop making harmful plastics and switch to reusable items to decrease waste. We can reduce food waste, and eat less processed foods. If every person were to make small changes in his or her day-to-day routine, it would have a monumental impact, especially if we can talk knowledgeably about it and convince others of the importance of climate change issues.

But if we don’t make these necessary changes, climate change will continue accelerating. Soon, villages like Shismaref and Kivalina, Alaska will be underwater and more communities throughout the rest of the United States will also face imminent threat. Now is the time to work to stop climate change. If we don’t, the world we live in could literally melt away.

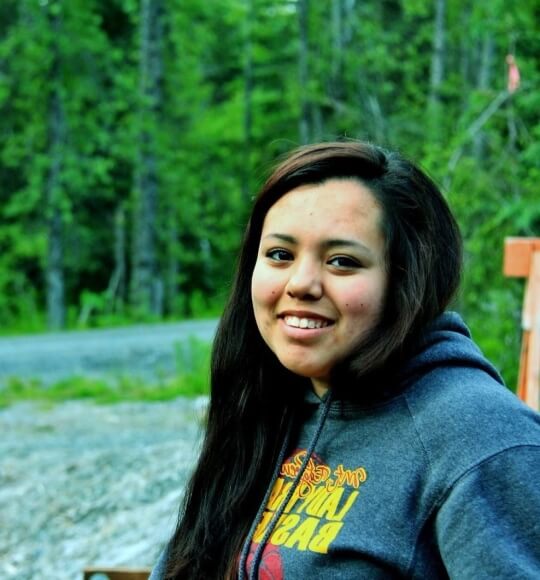

Macy Rae Kenworthy, originally from Kotzebue, spent a majority of her childhood across the Kotzebue Sound at her family’s camp in Sisaulik where her love for the outdoors originated. She graduated from Mt. Edgecumbe High school in Sitka, where her passion for science grew. Macy had the opportunity to participate in internships with the National Park Service through the Alaska Native Science and Engineering Program (ANSEP) and Student Conservation Association (SCA). Macy is currently a sophomore at the University of Alaska Fairbanks pursuing a double major in Chemistry and Secondary Education. In the future, she plans on teaching high school science and continuing my work in a conservation field.

Macy Rae Kenworthy, originally from Kotzebue, spent a majority of her childhood across the Kotzebue Sound at her family’s camp in Sisaulik where her love for the outdoors originated. She graduated from Mt. Edgecumbe High school in Sitka, where her passion for science grew. Macy had the opportunity to participate in internships with the National Park Service through the Alaska Native Science and Engineering Program (ANSEP) and Student Conservation Association (SCA). Macy is currently a sophomore at the University of Alaska Fairbanks pursuing a double major in Chemistry and Secondary Education. In the future, she plans on teaching high school science and continuing my work in a conservation field.

Grok Nation Comment Policy

We welcome thoughtful, grokky comments—keep your negativity and spam to yourself. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.