I was in my own musical reverie, headphones on, purchasing some dinner ingredients in a neighborhood store, when I happened to look up and glimpse an acquaintance, an Orthodox woman, doing her own shopping. I do not know her well, but I know she sings, and her music has become a presence of its own in my life. One of her songs – a simple, well-known camp song – particularly, reverberates. From its very first notes, the song thrusts me directly into the flames of the Shabbat candles in my childhood home, thirty years past, where immediately, I twist and burn, spiraling upwards, caught up in sharp spasms of searing grief. Those white-wax tapered sentries, wicks ablaze, glimmers of light, reflecting off the beautiful braided-brass candlesticks. Those candlesticks which had belonged to my father’s mother, those candlesticks which my Mother gave away to my oldest sister, while the Yahrzeit candle we lit for the passing of my Father still flickered fresh on the mantel. With the departure of those candlesticks, I had felt a dual grief: the loss of my father and an eerie dislocation towards the faith, I had grown up with.

Today, seeing this woman whose music evoked my former life, I felt a new sense of impending grief, the tumbled weight of love and loss.

****

I have recently asked my soulmate, my partner in crime, the love of my life to marry me.

Of course, now that we are engaged, there is to be a wedding.

It will be a wondrous wedding, with none of that horrid squeak of inexplicable wrongness of my first religious nuptials. I was born into an Orthodox religious community; the plans regarding my future had been in place for years, written, signed and sealed in my yearly birthday cards, the blessing to grow up and build a binyan adei ad, a Jewish edifice of a home based on the laws of the Bible. I had been nineteen years old then, a virgin, a doll dressed up in a dress.

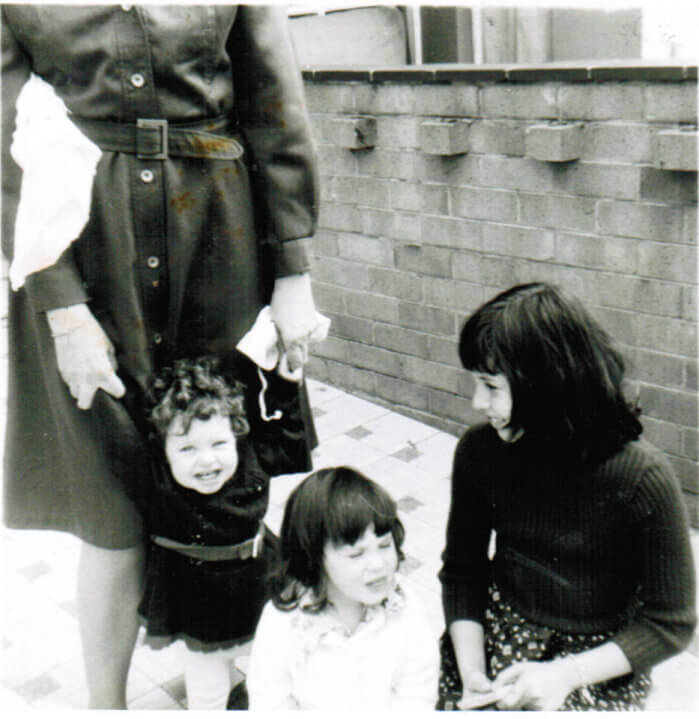

Thirteen years earlier, when my three excellent children and I left my Long Island religious community, it was with the sensation of doors being slammed shut and bolted behind us. Utterly bewildered, my children looked towards me, trying to understand why our friends, our community, and even their grandparents had forsaken us.

We moved to Brooklyn, to an area I knew was known to be tolerant of a LGBTQ family. My five-year-old son looked in dismay at the tiny, crowded two-bedroom apartment we were to live in.

“But Mommy, it doesn’t have any garden for me. Why did we have to move away?”

“I can’t get you a garden right now, but I promise you I will get you a garden as soon as I possibly can.”

We all had our moments, comforted by small joys. Ice cream trucks and a brand new cantankerous kitten.

“It is all right, and if it is not all right… it soon will be.” I told them.

There were years like that. Doorway years, where all we know abruptly closes behind us and we are suddenly plunged into the disorienting darkness of a hollow hallway for a moment.

I was frightened and lost, we all were, but the unbearable sweetness of being true and honest to what – and who – I had always been, gave me courage even in my fragility.

I grew weary of weeping like a beggar, for fragments of a world I could call home, so I reached outwards with my whole being to seek space, and found a wise, wide, expanse of universe to abide in. My legs were shaky to begin with, but with each step, I found my feet, my light, my sense of hope. I became firmer, brighter, stronger.

Then I found Shannon – in her heart I dwell, and she in mine – love thoughts, circle between us like seagulls, wings spread to the breeze.

My gaze is drawn to her, the way lightning calls to lightning during a storm and rivers of light spill from my eyes…

I have found this love, this love which is so profound, my blood rises in my veins a luminous flow which beats in sync with hers.

Every time I look at her, the hearth fire in my chest burns brighter. All I see these days are laugh lines and life lines, blood and breath. Substance, sustenance, sanctity.

Always steady, always warm, our hands hold an intricate, promise to the other, to love the other right.

A love like this, is beyond my bounds of cognizant reason.

There is to be a wedding. This time, I will wear dapper masculine garb, my lovely bride will wear a gorgeous wedding gown.

Of course, as with every momentous occasion, there will be that empty chair, that hollow space in the room where someone you love is missing from the table.

This time, there will be two empty chairs. One, for my father, gone 30 years now. And one for my mother, who is absent for another reason.

The first chair is familiar; I feel its sadness intimately.

I am not as accustomed to this other greater sadness. Or perhaps I am. Perhaps, this time I just cannot look away. Never has my invisibility been so blatantly obvious, this core disregard of all that I am. My mother is still alive and well, thank God(dess), but due to her beliefs or choices or principles, she will not come to our wedding.

I am also marrying out of the faith, and with a faith such as this, where rogue family is shaken off and trashed like paper goods after a picnic, honestly, it is without a backward glance. Far too often, we have gotten an urgent call, asking if we have any space in our home to shelter a young LGBTQ person with nowhere else to go. My fiance and I have sheltered as many as possible. There are always more in desperate need. There are children from religious families whom have been thrown out of their parents homes with nowhere to go, simply because they were gay. .

My mother, she says she “wants me to be happy,” she “wishes me well.” She likes Shannon, but she wants no part in it.

Of course she said too, “I love and support you but cannot attend your wedding.”

She is sure I will understand.

I refuse to understand. It does not work that way.

I have stood at the deathbed of my Father, watched how he fought for breath, how he struggled to spend every last moment with us.

I have stood at the deathbed of my Grandmother, how she faded away into a shadow of herself. I examined the way my gentle Grandfather watched over his dying wife with profound love, until her very last moment. I saw the visceral, atavistic grief of the old man, contracted in the corner of the room after she died. She was still right there, on the bed, covered by a sheet, and most of him was with her under that sheet, spirits curled around each other for all eternity.

After that day, he went virtually silent, slipping away incrementally. I was not there when he died but then again, neither was he.

We are ridiculously, terrifyingly, gorgeously mortal.

We have to reach out, capture and hold on to our moments of magic.

We need to allow happiness to unfold for us, little sparks of joy to rain down on us, like the long-ago purple jacaranda blossoms, that fell from the trees to collect at my feet like a perfumed carpet on the pavements of my native South-Africa.

Love, life, ideals do not nearly counter the fragile seconds we all have together. Ask yourself often, whom and what are most important to your existence. Then do your best to be where you know you need to be, to nourish those beings, distill those experiences. After you gravely tend to the inhabitants and dreams of your inner sanctum, there will be a greater depth and clarity of purpose for everything else.

Shay Benjamin is an ex- Hasidic parent of three incredible teenagers and three obstreperous cats. Shay, her fiancé Shannon, the kids and the cats, all live in in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Shay is kept busy working as a photographer, writer, and landlord. Shay also hosts LGBTQ religious youth, who have been displaced from their homes. Shay hopes to complete her degree in Clinical Psychology in the near future. On the rare occasion that she has down time, Shay enjoys reading, music, and art. Some of Shay’s favorite authors are Oliver Sacks, Anne Rice and Rumi.

Shay Benjamin is an ex- Hasidic parent of three incredible teenagers and three obstreperous cats. Shay, her fiancé Shannon, the kids and the cats, all live in in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Shay is kept busy working as a photographer, writer, and landlord. Shay also hosts LGBTQ religious youth, who have been displaced from their homes. Shay hopes to complete her degree in Clinical Psychology in the near future. On the rare occasion that she has down time, Shay enjoys reading, music, and art. Some of Shay’s favorite authors are Oliver Sacks, Anne Rice and Rumi.

Grok Nation Comment Policy

We welcome thoughtful, grokky comments—keep your negativity and spam to yourself. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.